“People kept thinking, ‘Oh, we can catch kids up later,’ and her big message was to start young and make sure the environment for young children is really rich in language.”

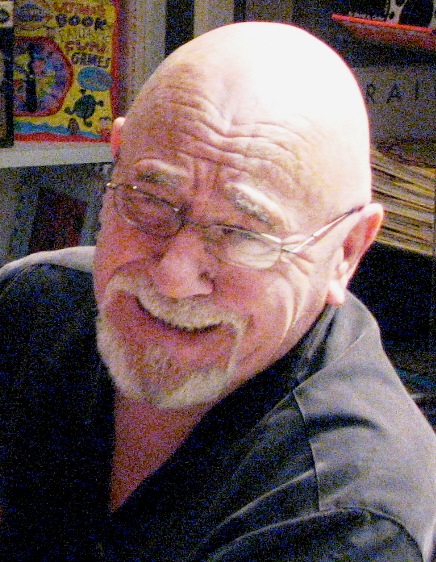

Betty Hart is one of my heroes. Thanks to her, we know this:

It is an unhappy fact that you can fairly accurately predict whether kids will graduate from high school by looking at their third grade reading scores. As Robert Pondiscio says:

I can think of no more urgent priority for K–12 education than getting as many children as possible to the starting line as readers by third grade. If that’s not a make-or-break issue for kids, it’s damn close.

Teaching vocabulary* is one of the most enjoyable parts of my job, so I’d do it anyway, but it’s because of Ms. Hart’s work that I do it with such urgency. And I bet she’d be pleased that her own obituary provides such a splendid array. The words we learned were: disparity, deficit, prevalent, transcribe, welfare, cumulative, touchstone, and jargon.

She’d also be delighted that one student, studying the chart, asked (unprompted) this astute question: “But what if poor parents talked to their kids more [than wealthy parents]?”** The title of a recent Washington Post article sums it up: “The most powerful thing we could give poor kids is completely free.”

In her honor, each student selected one of the above vocabulary words and created a (jargon-free) poster that could explain its meaning to a child.

*Shop talk: Bringing Words to Life taught me how to teach vocabulary. If my teaching bookshelf were on fire, that’s the book I’d grab.

**This led to a good discussion about averages, in which I emphasized that one could not conclude from the chart what all poor, working-class, or rich families do. In the course of this digression, we determined by how much my presence in the classroom raised its average age (noticeably), and we talked about how a visit from LeBron James would raise our average dunking skill and wealth.